|

|

|

|

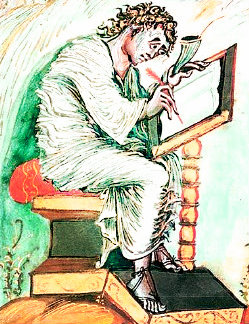

Manuscript Illuminator  The manuscript illuminator was a miniature painter and calligrapher who flourished from the Early Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Illuminated manuscripts are hand-painted and hand-written books. Many of the greatest illuminators of Europe were nomadic, traveling from country to country is search of commissions. The greatest illuminators of all time were the Limbourg Brothers. Manuscript Illumination started around the first century AD and is related to Egyptian papyrology (the art of ancient writing and painting on papyrus). The pages of the books were made out of goat or sheep skins - called parchment or vellum. The manuscripts were produced in monastic centers in the British Isles during the seventh and eighth centuries. According to Medieval historian, Julia De Wolf Addison, "Many different arts were represented in the making of a mediŠval book. Of those employed, first came the scribe, whose duty it was to form the black even glossy letters with his pen; then came the painter, who must not only be a correct draughtsman, and an adept with pencil and brush, but must also understand how to prepare mordaunts and to lay the gold leaf, and to burnish it afterwards with an agate, or, as an old writer directs, "a dogge's tooth set in a stick." After him, the binder gathered the lustrous pages and put them together under silver mounted covers, with heavy clasps. At first, the illuminations were confined only to the capital letters, and red was the selected colour to give this additional life to the evenly written page. The red pigment was known as "minium." The artist who applied this was called a "miniator," and from this, was derived the term "miniature," which later referred to Page 334 the pictures executed in the developed stages of the art. The use of the word "miniature," as applied to paintings on a small scale, was evolved from this expression.

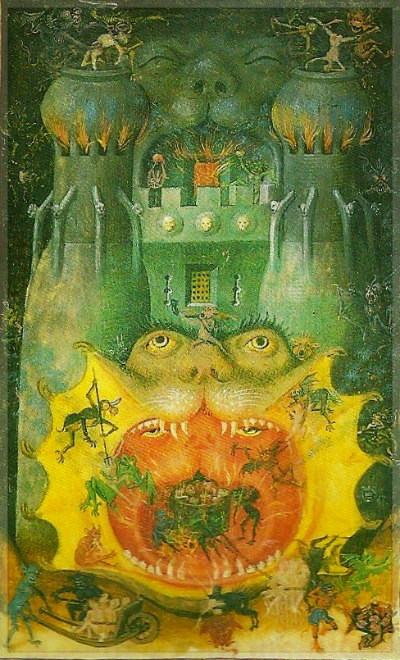

The early Christian artists favored morose and emaciated figures, hollowed cheeks and deep-set eyes, wide and feverish, filled with love for Christ. The miniature painting of the Irish, Gallic, and German monks was a melding together of painting and calligraphy. From the scrolls and flourishes purely calligraphic human forms are constructed. These early depictions were severe as judges with pitiless dignity, they stare from the pages like threatening tables of law, demanding submission, fear, and obedience, but according neither mercy, comfort, not redemption. As time passed illuminators added a touch of whimsy and humor. Julia De Wolf Addison asserts"In medieval times, the sense of humor in art was more developed than at any period except our own day. Even-while the monk was consecrating his time to the work of beautifying the sanctuary, his sense of humor was with him, and must crop out. The grotesque has always played an important part in art; in the subterranean Roman vaults of the early centuries, one form of this spirit is exhibited. But the element of wit is Page 351 almost absent; it is displayed in oppressively obvious forms, so that it loses its subtlety: it represents women terminating in floral scrolls, or sea-horses with leaves growing instead of fins. The same spirit is seen in the grotesques of the Renaissance, where the sense of humor is not emphasized, the ideal in this class of decoration being simply to fill the space acceptably, with voluptuous graceful lines, mythological monstrosities, the inexpressive mingling of human and vegetable characteristics, grinning dragons, supposed to inspire horror, and such conceits, while the attempt to amuse the spectator is usually absent."

With the triumph of Christianity, illuminators aspired to reawaken the divine spirit of holy figures rather than depict their physical qualities. Manuscript illumination was adored by kings and high-ranking nobles. By the fourteenth century the manufacture of manuscripts had become a profitable secular profession. Artists were regularly commissioned by royalty and members of the clergy. The best illuminators, such as the Limbourg Brothers, were celebrities, highly sought after. They received sumptuous gifts and money from their royal patrons.

Material to make to produce illuminated manuscripts were extremely costly, and included ground up precious stones and gold and silver leaf. The labour involved was tremendous and illustrated manuscripts often took years and sometimes decades to complete. Only the rich and powerful could afford to purchase such masterpieces. Most members of royal families had a collection of specially commissioned books. Illuminated books were status symbols and considered to be as precious as gold.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Require more facts and information about Manuscript Illuminators? Poke around every nook and cranny of the known universe for information this subject. Search Here ę HistoryofPainters.com If you like this page and wish to share it, you are welcome to link to it, with our thanks. If you feel you have worthwhile information you would like to contribute we would love to hear from you. We collect essential biographical information and artist quotes from folks all over the globe and appreciate your participation. When submitting please, if possible, site the source and provide English translation. Email to millardmulch@gmail.com |

The Meaning of Sacred Symbols in Paintings. Most prominently featured symbols and their meaning: